When Cesar Chavez, Gilbert Padilla, Dolores Huerta and others set out to build a farm worker movement in 1962, a newspaper—a “voice of the farm worker”—was high on their priority list.

In late 1964, Chavez was ready to launch the newspaper, to be named El Malcriado. He turned to Bill Esher to help produce and distribute it. Esher was a New Yorker whose dad was a teacher. Bill attended Syracuse University before heading west in youthful rebellion, ending up in the San Francisco Bay Area and gravitating towards the Catholic Worker community, which had a farm labor project based in Oakland. (Esher was not Catholic, but his parents supported Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker movement.) In Oakland, the Catholic Worker group sponsored a bus and transportation to help poor people there find and get to farm labor jobs. Esher drove the bus.

Esher also got to know Hank Anderson, a leader of Citizens for Farm Labor, one of the few groups championing reform of horrendous farm labor conditions. Through Anderson, Esher met Wendy Goepel, who was later the first full time staff person of the National Farm Workers Association, which became the United Farm Workers in 1966.

Goepel was working with then-California Governor Pat Brown’s administration. She reached out to Chavez as he began organizing in the early 1960s. She recruited Esher in 1964 to take a job picking melons in Kern County and documenting and reporting wage and labor violations. Goepel also introduced Esher to Chavez.

Chavez was immediately impressed with Esher, and asked him to move to Delano and begin working on the union’s new newspaper. By the time Esher accepted and came to Delano in early 1965, Chavez had produced the first issue of El Malcriado, in late 1964. Esher edited the second issue, and continued doing so through 1967.

The name El Malcriado reportedly hailed from a radical newspaper produced in Mexico during the Mexican evolution. The implication is of a rowdy child who does not offer due respect to his “betters” and who does not remain silent and docile. Chavez saw the paper as a benefit for union members, offered it by subscription and had it sold in barrio stories across the Central Valley.

Chavez had also sought out Andy Zermeno, a talented young Chicano artist with family ties to farm worker communities in Delano and San Jose. Zermeno created a series of characters that regularly appeared in the newspaper such as “Don Sotaco,” a short and initially humble and abused farm worker; “Don Coyote,” the labor contractor and field boss; and “Patroncito,” the fat Big Boss. Chavez and Esher would travel to Los Angeles to discuss cartoon ideas with Zermeno, who wielded his pen, brilliantly transforming ideas into visuals.

Since the newspaper had nearly no funds, Goepel provided Esher with a $50 monthly stipend out of her own pocket. Esher and Chavez sometimes worked in the fields together in the winter of 1964-65. El Malcriado emerged with finances apart from the union and with the Farm Worker Press as a separate entity and publisher.

Beginning with its earliest issues, El Malcriado drew links between the farm workers’ struggles in the United States and peasant struggles during the Mexican Revolution. Many in Delano in 1965 had personal experience with the revolution and its aftermath, plus the serfdom and pre-revolutionary hacienda system they compared with the exploitive system of California agribusiness. Chavez’s grandfather Cesario had escaped as a serf from the hacienda system of the Mexican state of Chihuahua in the early 1880s. Both Chavez and Esher enthusiastically admired revolutionary art that emerged from the Mexican Revolution. So woodcuts and pen-and-ink art graced covers of the newspaper.

“I remember Bill as a boy growing up amidst the difficult years of early organizing and later the turmoil of the Delano Grape Strike,” Cesar Chavez Foundation President Paul F. Chavez wrote in a letter to the Esher family. “It was only later when I came to appreciate the key role and sacrifices Bill and others like him made. As the years go by, we often don’t get to tell people until it is too late how much their contributions have meant to us, and to thank them for what they have done. Saying thank you doesn’t seem to be enough, but we shall always be grateful for all Bill did during those historic milestones in our movement.”

(Much material for this tribute is based on a 2009 essay by Doug Adair and Bill Esher from the Farmworker Movement website.)

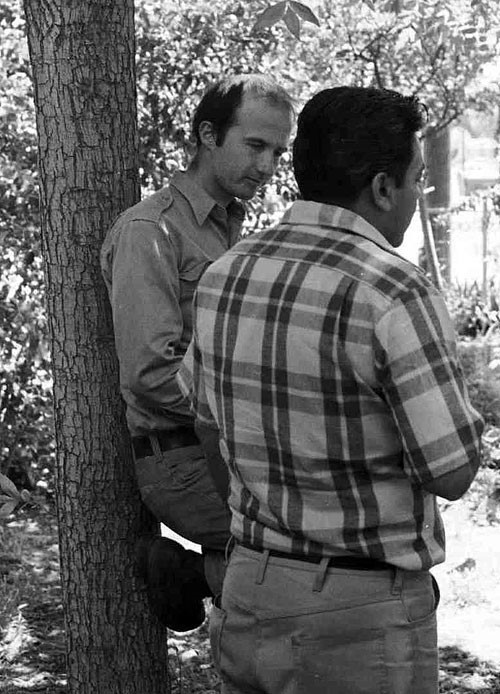

Bill Esher (left) with Manuel Chavez, Cesar Chavez’s cousin, with whom Esher worked during the early years of the farm worker movement. (Photo from Farmworker Movement website.)